Porty for Pottery, Paper and Pleasure?

As part of my research for my Porty Art Walk project, I have been investigating the town’s industrial heritage. I was struck by the postcard images of the pleasure beach full of people enjoying their holidays and the active industrial chimneys just behind the promenade.

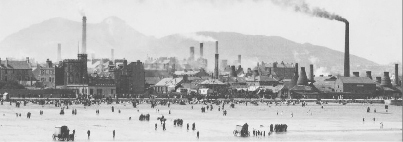

The idea of ‘sea-bathing’ dates from somewhere in the 17th Century and was becoming increasingly popular by the late 1800s. The beneficial properties of water as therapy or curative had long been expounded. Seawater was thought to have similar medicinal benefits to that of mineral water. It was often recommended to be drunk as well as bathed in. Portobello became popular for this type of activity. This image below highlights the contradiction. Succesful but polluting industry belching their bi-products into the very same air and water being promoted (via immersion or ingestion) to benefit one’s health and convalescence…

Portobello Shoreline: where leisure and industry meet? Image: Portobello Heritage Trust

Portobello’s industrial history precedes its incarnation as a place for pleasure… ‘Edinburgh by the Sea’. The rich deposits of clay discovered next to Figgate Burn made it an ideal spot for William Jamieson to first erect his brick and tile works in 1765. This industry evolved over time to include earthenware manufacture and the start of the famous Portobello Potteries. Production required a workforce and this brought aided an increase in population. This led to Portobello’s expansion from a village to the dignity of becoming a town.

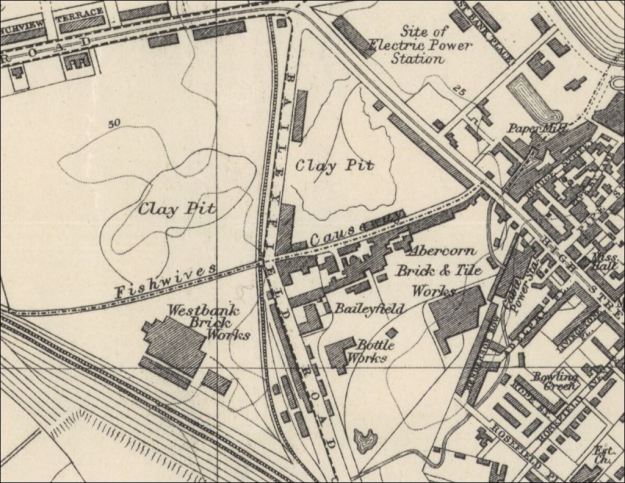

As well as the expanding pottery business Portobello also witnessed the coming (and going) of a variety of works manufacturing bottles, soap, mustard, lead products (pipes and paint) and the industry that caught my interest, paper.

Portobello Map, from the early 1900s, showing some of the industry in the town

The Paper Mill was situated in Bridge Street, next to the Figgate Burn. A potential source of power but a ready and available resource integral to the process of making paper. Originally the site (c.1783) housed a flax mill, and in the early 1800s was partly converted by James Smith (a Leith merchant) for making lead pipes and paint. Production of these products continued on the site until 1834. It then became a mustard factory until 1836 when it was converted once again, this time into a paper mill by Messrs Crighton & Co.

Money for old rope? Old rope discarded by the shipping industry provided a cheap source of hemp fibres for making brown ‘manilla’ paper. (Thank you, Roger, at Pen-y-coe Press for that ‘wow’ moment!)

The product was a common brown paper used for packaging and wrapping. It was not successful and the Paper Mill was purchased by Thomas Craig, one of four paper-making brothers who also established mills in Dalkeith, Moffat and Caldercruix. Thomas took over the mill in 1842 and after his death by his brother Robert until c.1850 when it was taken on by younger brother David.

He made additions and improvements to the buildings, methods and the quality of paper produced. All sorts of coloured papers were produced in large quantities. The success of this enterprise led to further alterations and investment in new equipment but this did not lead to commensurate success and the Craig era ended in 1871.

The premises re-opened under the ownership of Messrs Hunter and Aikenhead in 1872 and ran successfully for the next 17 years. Production was cannily changed to meet the increasing demand for papers used for newspapers and magazines. In 1889 the mill passed to Alfred and Frank Nicol and the brothers focused high-quality paper products. William Baird (Annals of Portobello and Duddingston, 1898, p450-45) notes that paper used for the Annals was produced at Nicol’s Mill and the brothers were ‘well known in the trade for their enterprise and skill, adopting modern methods and improvements’.

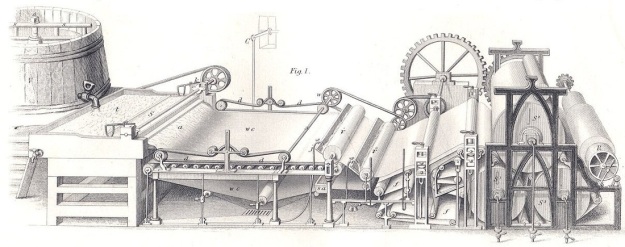

Fourdrinier Paper Making Machine. By 1820s most paper in the UK was being made on one of these.

The Mill had a single machine, it was the one purchased by David Craig and had an 81” deckle. Its size meant that almost any size of paper could be accommodated. The Nicols focussed on quality, smooth paper. It had no trace of ‘wire mark’ from the mould and did not lose bulk. This was achieved by super calendaring (the process of smoothing the surface of the paper by pressing it between hard pressure cylinders or rollers). The Mill supplied paper for book and magazine production to London, Glasgow, Birmingham, Manchester, India, Australia and the Cape. The steam-powered mill’s capacity in 1898 was 35 tons per week, with lengths of paper reaching 3.5 miles long. The steam power was coupled with the labour of some 80 employees, 30 of whom were women.

The Paper Mill was put on the market in March 1916 as a going business with a capital of £40,000.